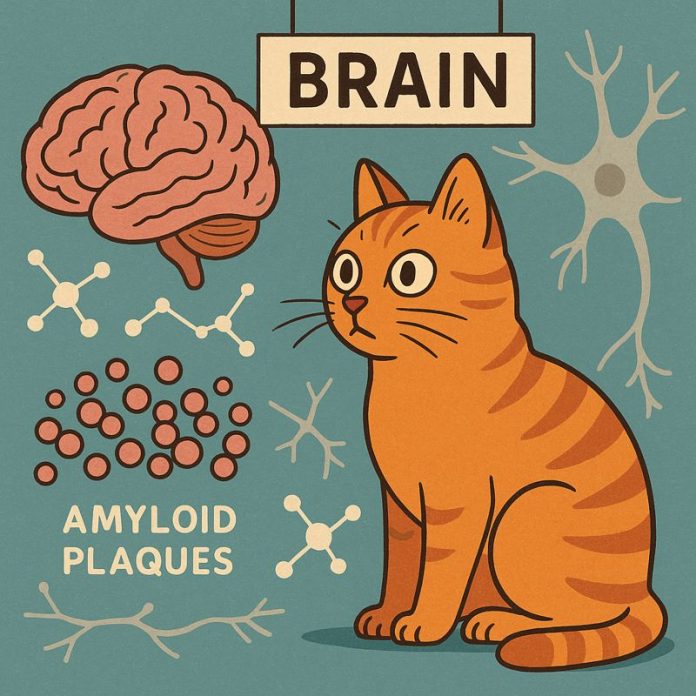

Cats and Alzheimer’s research now share a real point of contact, and it sits in the brain’s wiring. Researchers studying older pet cats found changes tied to amyloid-beta in synapses. These are the tiny contact points where brain cells pass signals, and they matter for memory and learning.

So the headline is simple. Ageing cats with cognitive decline can show brain patterns that line up with key Alzheimer’s features seen in people.

What the cat brain samples showed

Researchers examined brain tissue from 25 pet cats after death. Some cats were younger, some were older, and some had signs that fit feline cognitive dysfunction syndrome, often called cat dementia.

They found amyloid-beta inside synapses more often in older cats and in cats with cognitive decline. That detail stands out. Scientists often talk about amyloid plaques, but this work points at what happens right at the connection between cells.

Then they looked at immune-style support cells in the brain. They saw signs that microglia and astrocytes interacted with these synapses near amyloid plaques. They observed patterns that fit synaptic engulfment, meaning these support cells appeared to take in synapse material in plaque-rich areas.

So the story is not only plaques sitting in the brain. The story includes loss and disruption at the connection points that help the brain work minute by minute.

Why synapses sit at the center of Alzheimer’s questions

Alzheimer’s disease links to amyloid plaques and tau tangles, and it links to the loss of brain cells. Yet day to day function depends on synapses, so damage there can hit thinking early and hard.

This cat research puts synapses in the spotlight. It suggests amyloid-beta at synapses tracks with ageing and with cognitive decline in cats. It also adds a second layer. The brain’s cleanup cells may play a role near plaques, and that activity may connect to how synapses change over time.

Then there is the bigger point. A pet cat’s brain ages in a natural way. That makes it a useful window into how a living brain changes across years, not weeks.

Why cats can change how studies get done

Many lab rodents do not develop dementia on their own. Scientists often use engineered models, and those models help in many ways. Yet they do not match every part of human disease.

Cats can develop cognitive decline as they age, and that happens without genetic engineering. So researchers can study real-world ageing in a mammal that shares home life with people. Diet, light cycles, noise, stress, and sleep patterns can look more familiar than a lab setting.

At the same time, Alzheimer’s treatment research keeps moving. The FDA has approved anti-amyloid drugs for early Alzheimer’s disease, and doctors weigh potential benefits against risks like ARIA, a scan finding linked to brain swelling or bleeding. So stronger disease models still matter, and they can help researchers test ideas with clearer signals.

What this means for cat owners

Cat dementia is not rare, and age raises the odds. Published veterinary estimates often place dementia-like signs at about 28% in cats aged 11 to 14, and about 50% in cats aged 15 or older.

So what should you watch for at home. Look for changes that feel out of character, and look for patterns that repeat.

- More vocalizing, often at night

- Confusion, or getting stuck in corners

- Sleep schedule changes

- House-soiling

- Less interest in play, or sudden clinginess

- Shifts in social behavior with people or other pets

But do not jump to one conclusion. Many health issues can mimic dementia signs, and older cats face plenty of them. Pain, thyroid problems, high blood pressure, kidney disease, and sensory loss can all change behavior. So a vet check is still the clean first step.

If you enjoy research on how cats behave with people, this related piece may surprise you. Do cats meow more to men. a new Turkish study reveals a surprising difference.

Where the research goes next

This work points to a tighter target. Synapses may offer an early signal for brain decline, and support cells near plaques may shape what happens next.

So cats now sit in a helpful middle ground. They are pets with natural ageing, and they can support research that aims to protect memory in people. It is a practical link, and it may help on both sides of the leash.